Why is it so hard for the world to do something about climate change? This is not an easy question to answer. One of the main reasons is that climate change is a “wicked problem”—a serious problem that is complex and interdisciplinary in nature (Incropera 2016). These kinds of problems have multiple, interlocking causes that require us to tackle them from many different angles, including the science of global warming, economics and global inequality, government policies and enforcement, education and communication, historical and cultural patterns of daily life, and human psychology. In other words, tackling a wicked problem from one angle—while ignoring other issues at the same time—won’t get to the root of the problem and won’t make the kind of impact we need.

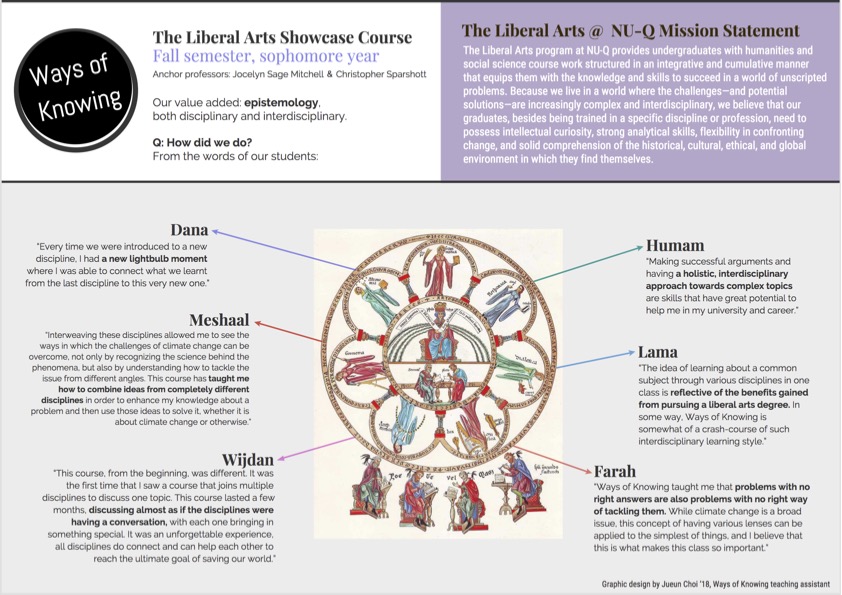

To tackle a problem like climate change, we need to start thinking across disciplines to synthesize real solutions. Together with Liberal Arts Director (and Professor of African American Studies & Theater) Dr. Sandra Richards and colleague Dr. Christopher Sparshott (Assistant Professor of History), we developed Northwestern University in Qatar’s required liberal arts course, “Ways of Knowing,” which explored climate change from multiple angles (earth sciences, history, political science, and communication). Developing and co-teaching this course for three years was one of my favorite experiences as a professor! I learned a lot from my co-professor and our guest instructors as well as from the intellect and curiosity of our students.

In my section of the course—the politics of climate change—I emphasized that political science has something particularly useful to contribute to this discussion of climate change problems and solutions—something called the theory of collective action. Collective action is when people work together toward common goals. But collective action is not something that happens naturally or easily a lot of the time, especially when goals are difficult and complex, such as how to solve climate change. Political science not only gives us a theoretical understanding of collective action problems, but it also suggests practical ideas for how to overcome these problems and get people to work together successfully.

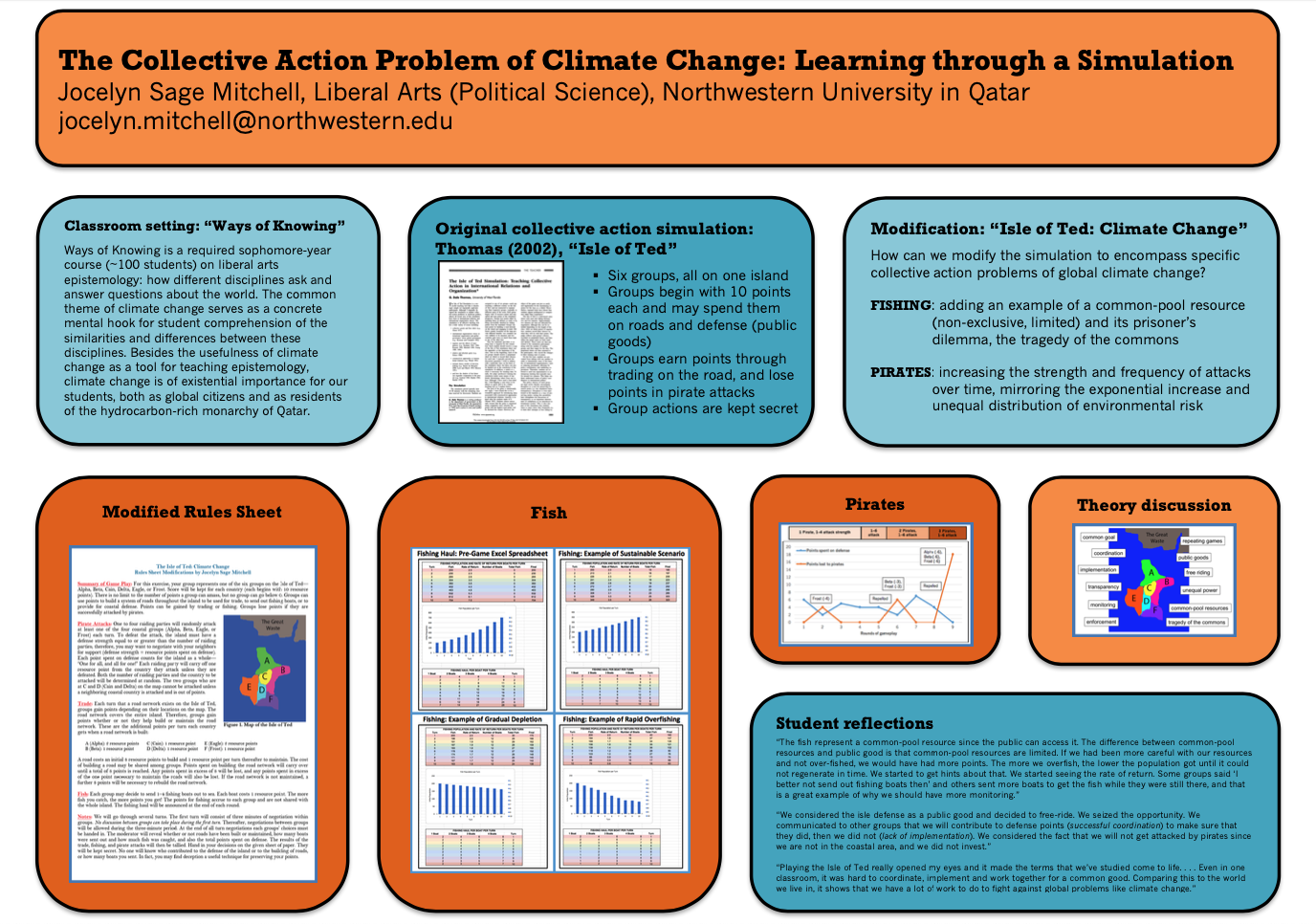

I had a lot of fun teaching our students about how collective action problems arise—and what we could do to solve them—through an in-class simulation, which is basically a game we get to play together that teaches us something at the same time. This in-class activity built on a classic collective-action simulation called “The Isle of Ted,” in which six groups are on an island, making decisions each round about how to increase their points and protect themselves from attacks. My activity was called “Return to the Isle of Ted,” because I added more components to the original game, like fishing boats and increased pirate attacks, to make the simulation more relevant to the collective action problems of climate change in particular.

Poster presentation at Northwestern University TEACHx 2019. Downloadable teaching materials available online.

The activity is fun! In their groups, students pretend they are on this island and make decisions together about whether to build roads for trading, send boats out for fishing, or contribute to the communal defense against attacking pirates. Each round, decisions have consequences for the individual groups and the island as a whole, and the students change their strategies depending on what they see others doing. After the activity is over, the class discussion helps the students connect the game to the concepts of collective action and how it relates to climate change. As one student reflected at the end of the political science unit: “Playing the Isle of Ted really opened my eyes and it made the terms that we’ve studied come to life. … Even in one classroom, it was hard to coordinate, implement, and work together for a common good. Comparing this to the world we live in, it shows that we have a lot of work to do to fight against global problems like climate change.”

I’m proud that my teaching simulation has been published—open-access, so everyone can read it free of charge—by PS: Political Science and Politics, one of the journals of the American Political Science Association (and you can access the short Kudos abstract here). And my simulation is also highlighted in the Syllabus Bank of the Climate Solutions Lab of Brown University’s Watson Institute of International and Public Affairs! Most importantly, I really enjoyed playing this game with our Ways of Knowing students, and I thank them for their interest, enthusiasm, and good humor!