South Park’s Season 13 / Episode 14 is the perfect example of how small individual decisions can result in giant collective disasters. Of course, since it’s South Park, it’s a gross example, so prepare yourself! In this episode of South Park, the boys go to a water park. Many individuals at this water park, including some of the main characters, make the decision to pee in the pool rather than inconvenience themselves by getting out of the water and finding a bathroom. In doing so, each individual assumes that their small action will not affect the greater whole. Inevitably, the entire water park’s ecosystem comes crashing down in a literal wave of urine, with total destruction of the water park and the (oft-occurring) death of Kenny.

When individual interests (staying in the pool, having fun) take priority over communal interests (the safety and sanitation of the public water park), these individual effects can multiply until the common good is destroyed. In political science, this outcome is known as the tragedy of the commons, a phrase from a famous 1968 article in Science by Garrett Hardin. It is a true tragedy, because the individuals do not start out with the goal of ruining the common good (technically, a “common-pool resource”). No one wanted to ruin the water park! The best-case scenario for each person is that they can fulfill their own selfish interests while everyone else plays by the rules, thereby ensuring that the common good continues. But of course, if each individual person makes the same calculation, then the common good will be destroyed.

South Park’s tsunami-of-urine makes us laugh, but the tragedy of the commons is a very serious problem with real-world consequences, including climate change. If each person, community, and country continues to prioritize individual interests over the common good, our environment as we know it will continue to become more and more uninhabitable for human life. Ultimately, climate change is not about the destruction of our earth. Our earth will continue. Climate change is about the destruction of our species’ ability to live on this earth.

Certainly, an inhabitable earth is a crucial common good for us all. But in their February 2022 report on the impacts of climate change, the IPCC (the UN’s scientific panel on climate change) offered its “bleakest warning yet” that we are running out of time to transform our global economy and remain below a warming of 2 degrees Celsius. And the latest update to the progress of the Paris Agreement (from the UN Climate Change Conference in November 2021) shows that, instead of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 25-45% by 2030, the world is set to increase these emissions by almost 14%. These data raise the fear that international agreements cannot solve this problem.

Political science to the rescue? Well, maybe? The fact is, political science has some useful insights that could help us understand how to change individual interests to better align with the common good. One of those insights is about the power of making it local.

Question: What if local communities can do a better job of governing themselves and solving their collective climate issues than large-scale international efforts?

Dr. Elinor Ostrom, a political scientist at Indiana University, won the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2009—the first woman to do so—for her work on how communities succeed or fail at managing common-pool resources like pastures, forests, and waters. She used real-life examples from around the world—Switzerland, Kenya, Guatemala, Nepal, Turkey, and Los Angeles—to show how communities cooperate to share public resources and assure their survival for today and the future. Successful communities do this through a combination of structured rules and local social norms. And Elinor Ostrom’s big idea was that by bringing it down to a small size—local communities, businesses, households, and individuals—we can create the kinds of incentives and understandings that can make resource governance work.

This is the kind of approach that Michael Bloomberg and Carl Pope take in their 2017 book, Climate of Hope. Bloomberg was the mayor of New York City from 2001 to 2013, and Pope was the executive director and chairman of the Sierra Club, an environmental organization, for 15 years. They write:

“When scientists set out to rid the planet of disease, they don’t attempt to cure every disease at once, and they don’t expect a single research team to come up with all the answers. Instead, by working in many different labs all over the world and sharing their discoveries, teams of scientists zero in on a single type of disorder, study its characteristics, research its causes, and experiment with cures. Meanwhile, other teams of scientists tackle other diseases. It’s a strategy that has led to countless breakthroughs—and it’s the same approach that we should be taking with climate change. The changing climate should be seen as a series of discrete, manageable problems that can be attacked from all angles simultaneously. Each problem has a solution. And better still, each solution can make our society healthier and our economy stronger.” (p. 3, emphasis added)

One example of this strategy is the success of PlaNYC in New York City. Why do Bloomberg and Pope write, “Cities are actually the key to saving the planet”? (p. 20) They have three reasons: (1) cities account for 70% of worldwide greenhouse gas emissions; (2) mayors are more pragmatic and less ideological than national politicians; and (3) climate change policies are linked to faster economic growth. PlaNYC started with a projection: By 2030, NYC would have one million more people living in the city than in 2000. At the same time, NYC is a coastal city, with 520 miles of waterfront (making rising sea levels a major concern). So Bloomberg’s administration began reimagining NYC for the 21st century. The group held dozens of public forums and town hall meetings, created an interactive website, and facilitated discussions with more than 150 advocacy groups, scientific advisors, and partnerships. The end result was the creation of PlaNYC: 127 initiatives aimed at creating the world’s most environmentally sustainable city.

By the time Bloomberg left office in 2013, NYC’s carbon footprint had shrunk by 19%, putting the city ahead of schedule to reach a 30% reduction by 2030, even as the population continued to grow. Air pollution fell to the lowest levels in half a century, and NYC created a record number of jobs.

What is the main takeaway from the success of PlaNYC? As Bloomberg and Pope write, “America’s ability to meet our Paris climate pledge doesn’t depend on Washington.” (p. 35) Rather, meeting our greenhouse gas reductions depends on cities, businesses, technology, and citizens. And this local focus on cities is a trend around the globe, as seen in the work of the C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group, which focuses on “thinking locally, acting globally.” The C40 group represents 90 of the world’s greatest cities (650+ million people) and produces a fourth of the global economy output. The upshot: If you fix cities, you fix climate change!

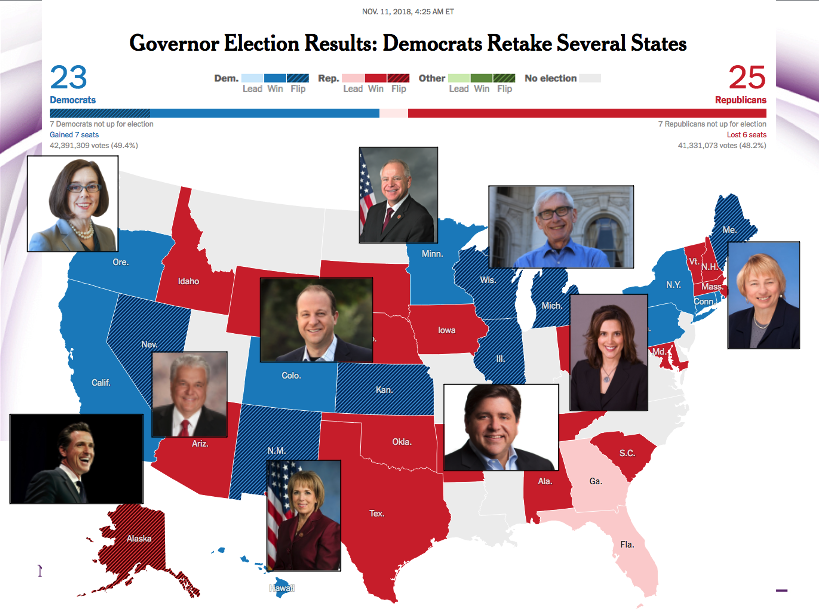

And it’s not only at the city level, but at the state level too, where big changes can happen. A lot of times, people focus on the national US elections—for president and Congress. But because the US is a federation, with lots of power reserved for the states, each state’s governor has immense power to chart local environmental policy and make a big difference. In the 2018 midterm elections, at least 10 candidates for governor won their races by campaigning on renewable energy policy for their states! Examples include Steve Sisolak in Nevada, who supported the successful ballot measure for Nevada to get half the state’s power from wind, solar and other renewable sources by 2030. There’s also Tim Walz in Minnesota and Michelle Lujan Grisham in New Mexico, who have both pledged to get half their states’ power from renewable sources by 2030. And Janet Mills, the first woman governor of Maine, is one of several new governors—including Jared Polis of Colorado, Tony Evers of Wisconsin, J.B. Pritzker of Illinois, Gretchen Whitmer of Michigan, and Kate Brown of Oregon—who have pledged to get ALL their state’s energy from “clean” sources by 2050. Gavin Newsom of California has pledged to go completely carbon-free by 2045!

These states and their governors are a great example of not needing to coordinate on the international level—or even the national level—to still create very big changes and reductions to greenhouse gas emissions. So one insight from political science is very relevant as we approach the 2022 elections and beyond: local (city and state) politicians can make a big difference in climate change policy, so choose (and vote) wisely!

Note: Much of this material is originally from my political science lectures from our interdisciplinary “Ways of Knowing: Climate Change” course. I am available (and willing!) to present this material to a public audience!